Book About Organ Harvesting Atrocities Released in Czech Republic

(Minghui.org) American investigative journalist and author Ethan Gutmann arrived in the Czech Republic on January 8, 2016, for a week-long series of events to launch the Czech version of his book The Slaughter, and raise awareness of the Chinese regime's harvesting of organs from living prisoners of conscience.

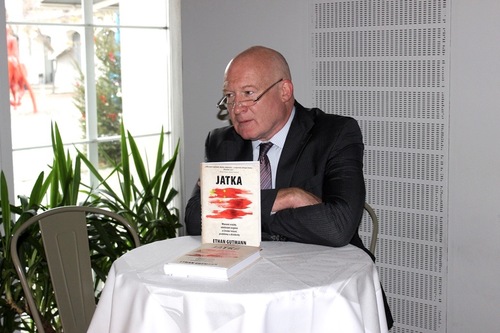

Ethan Gutmann with his book The Slaughter published in Czech. (David Jurik)

Ethan Gutmann with his book The Slaughter published in Czech. (David Jurik)

The Czech edition of the book was published in November 2015, the second translation after the German version. During the January events Gutmann presented his findings at two Czech universities, in the Parliament before the Subcommittee for Human Rights, and at several other talks.

Senator Patrik Kuncar commented after one of Mr. Gutmann's talks, “As for the forced organ harvesting of political prisoners in China, it is something inconceivable! I think it's important the public is informed about it in order to prevent these brutalities as much as possible. This is basically a parallel to what was going on in our country during communism, and it shows that every [instance of] totalitarianism is evil and eliminates its opponents in the most gruesome matter. And if there is any chance to make money on it, they will do it.”

Gutmann was working in Beijing in 1999 when the persecution of Falun Gong began. He quickly realized that Falun Gong had become the most important issue for the Chinese Communist Party. Seeing over the years how poorly the topic of Falun Gong and the persecution had been reported and misunderstood in the West, and how unbalanced the books written on the topic by Western scholars were, he embarked on a journey to investigate and write his own book. Years of painstaking research resulted in the publication of The Slaughter.

Gutmann originally intended to write about the conflict between Falun Gong and the Chinese Communist Party. However, as he interviewed many witnesses for the book, he realized that the forced organ harvesting was indeed going on in China, and that Falun Gong practitioners were the largest group victimized.

Problem of Medical Confidentiality

Gutmann said to the Subcommittee for Human Rights on January 12, “I ask only that you remove the privacy shield, the medical confidentiality, so that we get at least a sense of how many Czech citizens are going to China [for organ transplants]. And if there are Czech citizens going to China, then you can consider banning organ tourism to China.”

The issue of medical confidentiality hinders Gutmann and other investigators of forced organ harvesting in China. “This is something we come across all the time,” said Mr. Gutmann. “In individual countries, in parliaments, they keep asking us: How many of our people travel to China for their organs? The answer is, we don't know, and it is because of medical confidentiality.”

The day before Mr. Gutmann spoke at the 2nd Faculty of Medicine at Charles University, one of the doctors present, an official from the Transplantation Society, said that two of his patients, both of Vietnamese origin, have traveled to China to receive kidney transplants. This suggests that organ tourism to China is happening everywhere, and is not limited to only wealthy Western or Asian countries.

“We will be looking into the avenues of how to deal with this issue in the Czech Republic,” said MP Marketa Adamova, chair of the Subcommittee for Human Rights of the Chamber of Deputies.

Gutmann explained that in China, a “donor” has to die in order for someone else to receive a new organ, including kidneys. He estimates that up to 75 percent of the prisoners used as organ sources are prisoners of conscience, mostly Falun Gong practitioners. These people are killed by Chinese surgeons on the operating table, said Gutmann.

“A moral and ethical line has been crossed here. Doctors are the most respected members of society across the world. To turn them into these mass murderers is a terrible thing,” said Gutmann. He, along with other dedicated investigators and doctors, has been working hard to push individual countries to minimize their contributions to the problem, and ban organ tourism to China.